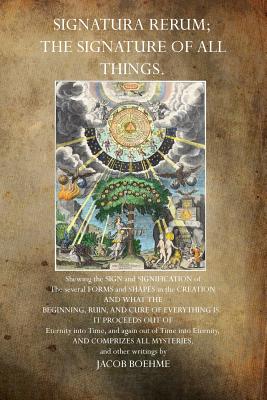

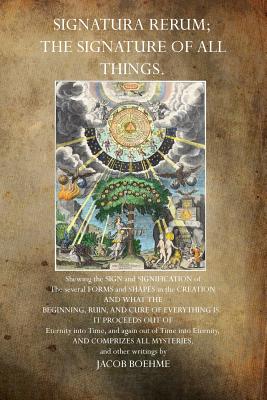

Thank you for checking out this book by Theophania Publishing. We appreciate your business and look forward to serving you soon. We have thousands of titles available, and we invite you to search for us by name, contact us via our website, or download our most recent catalogues. THERE are few figures in history more strange and beautiful than that of Jacob Boehme. With a few exceptions the outward events of his life were unremarkable. He was born in 1575 at the village Alt Seidenberg, two miles from Goerlitz in Germany and close to the Bohemian border. His parents were poor, and in childhood he was put to mind their cattle. It was in the solitude of the fields that he first beheld a vision, and assuredly his contemplative spirit must have been well nourished by the continual companionship of nature. Now in the study of mysticism we soon find the essential experience of all mystics to have been identical, and that among them is no figure more representative than Jacob Boehme: so that when we read this book we are like men who from the vantage-point of one of its highest hills can see below and around them the whole expanse of a beautiful and unearthly island. If it allures us we shall then delight in exploring its verdant valleys or spirit-peopled woods or quiet starlit gardens, and all the mysterious birds and blossoms that fly or flutter within them; but if it does not seem attractive we can push off and sail for another country. By no true philalethe can mysticism be honourably ignored. It is either the noblest folly or the grandest achievement of man's mind. Alexander and Napoleon were ambitious, but their ambition dwindles to insignificance when it is compared with that of the mystic. The purpose of the mystic is the mightiest and most solemn that can ever be, for the central aim of all mysticism is to soar out of separate personality up to the very Consciousness of God. So well, indeed, had Roman Catholicism taught those who were religious the insignificance of the human soul that few among the European mystics of the Middle Ages or the Renaissance were so brilliantly conscious that they could cry out boldly with Meister Eckhardt, "I truly have need of God, but God has need of me." Often they shrank from the ultimate experience, wholly worshipping God indeed, but retaining ever a sense of separateness. Their very humility was the final veil of egotism which they dared not rend. Jacob Boehme, the last of the great European mystics, having imagined the